How the Smart Grid Will Energize the World

By David Mayne, Director of Business Development, DIGI

Abstract: Technology is rapidly changing the way we approach almost everything we do in life. A variety of influencing factors are causing utilities to get on-board with the latest Smart Grid technologies and placing consumers in the driver seat when it comes to energy conservation. There are a myriad of approaches being explored to provide everyone with accurate data and allowing something as complex as the energy grid to be able to operate efficiently and intelligently. By staying flexible and using a variety of communication resources, the Smart Grid will mean many things to many people.

What is the Smart Grid?

The "Smart Grid" is a term that most of us had never heard five years ago. Today, this phrase generates 2,514,000 hits on Google®, is the subject of state and federal legislation, and was even highlighted on a television advertisement during the 2009 Super Bowl! The Smart Grid is referenced as a possible solution to terrorist attacks, a method for minimizing climate change, and a means of stimulating sustainable economic growth for the global economy.

One would think that a technology delivering wide ranging impact on national security, the environment and the economy would be clearly defined and well understood. Further investigation will highlight that this is not a single technology, network or solution, but rather an ecosystem that is evolving and will continue to evolve over several years. The goal of the Smart Grid is to provide communication, information and control to as many points on an energy distribution network as possible, maximizing the efficiency, reliability and security of the system. The specific requirements will vary, largely driven by the needs of the devices and applications associated with each sub-system.

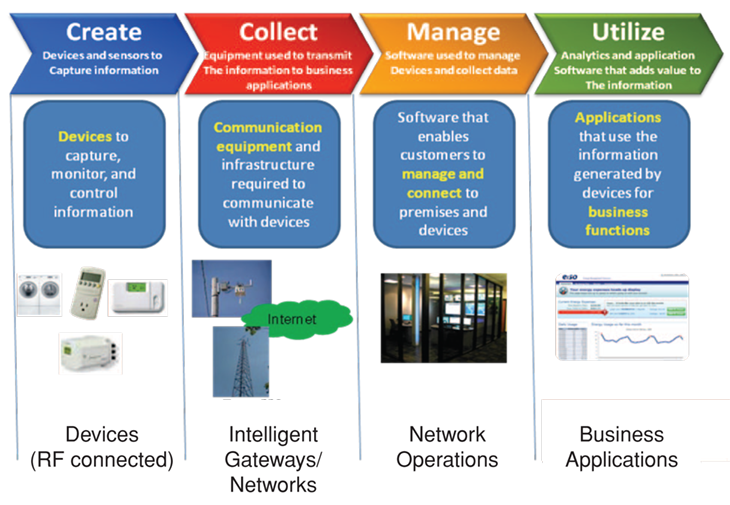

DIGI has identified four characteristics that are common to all aspects of the Smart Grid:

- Create devices and sensors to capture information and provide control

- Collect communication devices and networks that provide connectivity to the devices

- Manage a network operating center for managing the system

- Utilize applications that monitor and control the devices

Specific bandwidth, latency and cost targets will vary greatly for each device on the network, but the core characteristics remain consistent. The industry is developing a system that provides actionable information from a broad range of devices, and software solutions that enable stakeholders to provide time sensitive responses to the changing demands of the distribution grid.

This white paper focuses on the importance of maximizing flexibility at both the device and application side of the Smart Grid. This system will continue to evolve and will demand solutions that include wired connectivity, public wireless and private wireless networks. The system will be defined as much by the applications connected to the Smart Grid as they are by the network technologies utilized in the deployment.

What Is the Smart Grid?

Ask a person to define the Smart Grid and you will receive a wide range of answers. If you ask a meter engineer, they will suggest it is Advanced Metering Infrastructure (AMI). If you ask a Protection and Control Engineer, they will suggest it provides substation and distribution automation services. A Control Room Operator focuses on the benefits of distribution and outage management. The responses by each group are 100% accurate, and demonstrate the wide ranging requirements of this emerging technology.

EPRI defines the Smart Grid as, "A power system that serves millions of customers and has an intelligent communications infrastructure enabling the timely, secure and adaptable information flow needed to provide power to the evolving digital economy." (EPRI® Intelligrid 2007)

EPRI further suggests that the Smart Grid represents the integration of an energy distribution network and information infrastructure appropriate to provide communication and control to a wide variety of locations. Doing so enables a broad set of services that benefit both utility operations, and consumers of energy.

These opportunities have opened the door for an extensive list of companies, both large and small, to introduce communication solutions and applications. Each offering attempts to stake claim to providing a unique set of benefits to the Smart Grid.

The reality is that many communication solutions - public, private, wired and wireless - all can and will contribute to the overall ecosystem. Each technology provides a unique set of performance, cost and reliability goals that differentiate, but do not diminish, their contribution to the overall system. The challenge is not in defining the technology, but rather in efficiently and securely connecting these devices to their associated applications. The architecture will enable continued innovation in Smart Grid applications such that a solution launched in 2017 can communicate with a device deployed in 2009. Utilization of "middleware" connectivity management solutions is a significant component that enables continued innovation in these deployments.

Why Does a Consumer Care?

Most people are well informed about some forms of energy use, and completely blind to others. If you ask a person what kind of mileage their vehicle gets, they can likely provide an answer. Ask them what the price of gasoline is, and again they can offer a fairly quick and accurate response. Consumers clearly understand the cost of driving and the impact it has on their wallet and the environment. To help manage this, automakers provide a dashboard that indicates fuel levels and in newer vehicles even consumption data. This information allows the consumer to actively participate in managing their energy usage.

If we turn the discussion to the person's home, the responses are very different. How many kilowatt hours do they use in their home? Very few people can respond. What do they pay per kilowatt hour? Again, few can answer. How much money do they save if they raise their thermostat two degrees in the summer? If their entire neighborhood purchased a plug-in Hybrid Electric Vehicle (PHEV), would their lights dim when everyone returned home from work and plugged them in? These are questions few people are comfortable discussing.

One of the key goals of the Smart Grid is to allow energy consumers to participate in decisions regarding their usage. Whether the goal is to save money or to help the environment, the system must provide near real-time communications and control services.

Implementing an application like those highlighted in Figures 3 and 4 does not mandate use of any specific communication technology. The core requirements are not defined by a 3G cellular network, a ZigBee® radio, or any other network technology. They require a consistent and reliable means of passing information from the application to the associated devices. DIGI launched a product called iDigi™ Energy to provide this information pipeline. The goal of this system is to remove the complexities of the network technology, topology and management away from the core energy application. This allows new services and communication technologies to be rapidly adopted - enabling the Smart Grid to gracefully evolve through continued innovation.

These energy dashboard solutions not only provide consumers with a heightened awareness of their energy usage, but as the Smart Grid matures, time-based rates will become much more prevalent. If the environmental and convenience benefits are not sufficient enough to drive market adoption, the economic motivators of time-based energy rates will ensure wide-spread usage of these tools. Manufacturer-sponsored studies have demonstrated an 11-20% reduction in energy consumption through the use of an in-home display or other energy management portal. Benefits to the grid include both a reduction in peak-load and load shifting - both are key benefits provided by the Smart Grid.

Why Does a Utility Care?

Many utilities today define several groups or divisions that manage software, communications and grid measurement/ control solutions optimized to deliver results for their specific department. Sharing information on a real-time basis between each of these technology "silos" is extremely difficult, impractical or simply impossible.

One of the key objectives of the Smart Grid is to integrate all systems onto a single Operational Service Bus - such that data can be shared and the information captured is actionable across the entire utility infrastructure. By implementing this transition, a utility can leverage real-time meter consumption data to facilitate intelligent decisions on grid level control circuits. If the metering system reports that the load of 10 meters served by a distribution transformer exceed the rating for that device, then the Smart Grid could elect to shut down (curtail) consumption from selected appliances. This action improves the safety and reliability of the affected transformer. This is just one example of the operational benefits these systems are envisioned to provide.

Today, utilities offer Demand Side Management programs to many customers. Through these programs, a customer will receive a reduction in their energy bill in exchange for allowing high use appliances to be turned off by the utility periodically. The consumer has little say as to when where, or how these actions are taken and the utility applies these load control events on a system wide basis - not targeted to specific areas of the grid that are running at peak capacity.

By improving the communication backbone of the grid and by integrating the metering, load management and distribution automation functions, intelligent controls can be performed. The utility can use interval meter data from the AMI system to determine regions that are nearing maximum load. Software can optimized to review energy factors of a home enabling the utility to pre-cool in advance of a peak load condition or perform other functions to shift load to different times of the day. Consumers can be notified through email, web-portals or in-home displays of pending events - and take action to help shift loads and minimize their energy bill. This might include turning off a pool pump, water heater or PHEV charging system.

Each of these actions requires communication, control and integrated software solutions. These are the defining elements of the Smart Grid and the focus of innovation in the coming years.

Time = Money

The combined forces of all networking technology utilized in the Smart Grid are aimed at time-sensitive collection of energy consumption data. Whether utilizing power-line carrier, fiber, cellular or proprietary wireless communications, the goal is to determine what energy is being used, and more importantly, when! If I commute to the office during rush hour, I use far more gas than in the middle of the day; hence my costs (environmental and economical) are much higher than if I try to shift my driving patterns. The same is true for energy consumption. If I use electricity during the "electrical rush hour," the cost to the utility is significantly higher - yet in most cases they are unable to pass that extra cost on to the consumer.

The Smart Grid is the first broad reaching initiative enabling utilities to better map costs to price, which in turn will strengthen support and adoption of time-based rate structures. This will greatly increase the need for "energy dashboard" tools communicating rate and consumption data to consumers, and will rapidly expand the number of people actively participating in load shifting programs.

Once again, these challenges do not define a specific networking technology - but rather an information and control ecosystem that will utilize many networks - both wired and wireless - to promote an interactive, reliable and efficient energy delivery grid.