World Wide What? An Honest Look at the State of the Internet of Things

By Michael Parks, P.E., Mouser Electronics

Featured Suppliers

Featured Products

Related Resources

Every day over 3 billion people use the Internet to connect with each other and to share ideas. According to many technologists, an Internet of Things (IoT) will soon change our lives in ways that are perhaps more nuanced but still just as significant. IoT promises a simpler life for consumers by taking the “things” that we use every day and embedding them with the ability to sense, process, interact, and communicate with us, their environment, and each other. The resulting intelligence and connectivity will allow for unprecedented automation. Free from having to remember countless daily chores such as locking doors and turning off lights, we will instead focus on more important aspects of life. However, there are significant implementation challenges that lie beneath the surface of this simple notion. In the end, will IoT deliver the serenity it promises or will it implode under the weight of lofty ambitions?

Defining the Internet of Things

Imagine it is the year 2027. Your phone’s alarm clock app begins playing light music. As you enjoy the last few minutes of peaceful slumber, all the “things” in your home begin to request data from each other. Bleary-eyed, you slowly make your way to the shower. After brushing your teeth you discard an empty tube of toothpaste. The trashcan promptly detects the RFID tag of the newly added contents, accesses your Amazon Pantry account and orders more toothpaste. As you walk out the door, your umbrella has received word that it is going to rain today and is blinking a series of LEDs embedded in its handle to remind you to take it with you.

The point of this story is to provide some context as to what is meant by “things” when discussing the Internet of Things. This barely scratches the surfaces of the possibilities, but the notion of an intelligent umbrella and trashcan makes it clear that the term “things” really does mean everything, that is, if the IoT is to be fully realized.

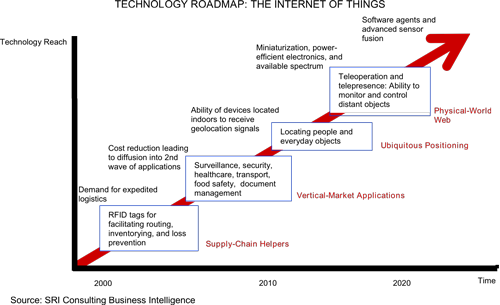

Figure 3: Technology Roadmap: Internet of Things Source: SRI Consulting Business Intelligence - Wikipedia.org

The term “IoT” was originally coined in 1999 by British technologist Kevin Ashton. It can be argued that the some concepts underlying IoT, such as the notion of automation through software and electronics, dates back decades. Even though the ideas have been around for a while, several underlying technologies are only now reaching a maturity and price point conducive to make the leap from concept to reality for IoT. Such technologies include small and reliable sensors, low-cost microcontrollers and pervasive high-speed wireless Internet. And like trying to define “the Cloud,” there is no shortage of definitions. Despite the nearly countless definitions of the Internet of Things, they all share five fundamental concepts:

- The ability to sense and digitize various attributes of the environment such as temperature, lumens, and barometric pressure, among others.

- An IoT device must be able to fuse discrete sensor data, process the data gathered, and then decide on an action to take.

- The IoT device may interact with the environment through any number of actuators, such as activating an electronic door lock.

- IoT devices must be IP-addressable. IoT devices must be able to communicate what they are “seeing” through their sensors with other devices, web-based services, and to humans over the Internet.

- All of this must be accomplished without requiring the direct interaction or intervention of a human.

Of these five tenets, it is the fourth concept that presents the greatest challenge to mass adoption of the Internet of Things.

Will the Internet of Things Become a “Thing”?

IoT does not represent a revolution of the fundamentals or even the invention of new technologies. Embedding intelligence, sensors, and actuators into devices, though not a trivial matter, is not such a great engineering problem any longer. The modern smartphone contains perhaps a half-dozen sensors and processing horsepower that would rival the high performance desktop of just a decade ago. From the perspective of making “smart” devices that can sense and interact with the world, the IoT is very achievable. As alluded to earlier, the challenge is to interconnect things on an unprecedented scale. It is this issue prevents the IoT from mass adoption.

The Internet has been a democratizing force, conquering the divides of operating systems and CPU architectures so that everyone can connect regardless of their particular computer specifications. So you might ask, “How can communications be an issue for the Internet of Things, if the devices that makeup the IoT are supposed to be talking to each other over the Internet in the first place?” In other words, isn’t the internet enough for these devices to communicate with each other? To answer that question without devolving into a technical discussion of the Open Systems Interconnection model (an essential networking concept) consider the concept of accessing the World Wide Web via a browser versus interacting with a social networking app on a smartphone. Both might rely on the Internet, but there are fundamental differences that boil down to an analogy of speaking different languages.

The World Wide Web, which sits atop the lower protocols that govern the Internet, has had much success in crossing divides of different operating systems and web browsers. By using standards such as HTTP, HTML, and TCP/IP we can ensure that (the idea of browser plug-ins aside) if a web site is viewable in one browser it should be viewable in all.

On the other hand, consider apps such Apple FaceTime and Google Hangouts. Both are functionally similar, allowing for the transmission of two-way, live video over the Internet. While they both use common protocols to a certain point, not all protocols are common between them, and thus you can’t (currently) contact a friend who uses Hangouts via FaceTime. This is the same reason why Apple and Android have their own “marketplaces” of apps. Interoperation of a video chat program on both smartphones essentially requires a translator, which complicates things when you don’t have an exact translation for a specific word (or action, in the case of smartphones.) The same is true for the literally dozens of IoT products on the market today. IoT is following the app-based model of communication, eschewing the more universal web-browser model. The fact that IoT products are not built to be interoperable without kludged hacks and workarounds presents the most significant challenge to adoption of more smart devices in the consumer and industrial space. People will only tolerate a lack of interoperability to a point.

So is the IoT likely to become something useful and pervasive in society? As with all complex engineering questions, the best answer as of today is “It depends.”

Building the Bridges: How IoT Gets from Here to There

To gain some perspective on why this non-answer really is the best answer that can be proffered in the development of this nebulous entity many call IoT, we must juxtapose two worlds. World number one has had tremendous success in defining common protocols, and world number two, where common protocols remain as elusive today as they were 20-plus years ago.

The first is the world of web-based companies and services. Companies that play in the web-based ecosystem have over the last decade fought diligently for a more open and transparent Internet. With the adoption of HTML5, amongst all the major players in the browser market and companies that make their living on the World Wide Web, the Internet itself is a model for companies to realize that “a rising tide lifts all ships.” That is to say, as the Internet becomes easy to the point of being taken for granted by consumers, the more likely consumers are to use the Internet to the financial benefit of the entire marketplace.

Example (world) number 2 is the home automation and industrial control industries that are literally flooded with dozens of competing, proprietary, and non-interoperable protocols. In the home automation sector alone one will find several protocols such as X10, Insteon, UPB, KNX, ZigBee, and Z-Wave. Add to this building and industrial control systems, and there are literally dozens of additional protocols. But the technologies involved in home automation and industrial control are more akin to the Internet of Things then the World Wide Web. Thus, if we have not yet solved the interoperability issue across these two industries, it does not bode well for our ability to tackle the heart of the challenge: the common protocol issue that is necessary to realizing a fully interconnected Internet of Things.

Perhaps the path to an Internet of Things will be an iterative process. First, individual market segments will have to unite behind common protocols across competing companies. The automotive industry will have to adopt a universal protocol that lets cars talk to each other regardless of manufacturer. The home automation industry will have to finally adopt a universal standard so that consumers are no longer under the threat of vendor lock, where they are locked in to a specific protocol (and products) only offered by a specific vendor. In the end, they might just be forced to a common protocol if they wish to be smartphone compatible with the upcoming release of Apple’s HomeKit and/or Google’s Brillo and Weave products.

This strategy will result in many Islands of Things (namely the islands of Android and Apple), but it is perhaps a more tenable situation to start from, should innovative products demand a truly interconnected Internet of Things in the future. It will be far easier to build protocol “bridges” between a few, well defined “industry-specific” protocols than hundreds of competing, product-specific protocols. If these bridges are built, than the eventual likelihood of a complete Internet of Things is more likely.

The Barriers Preventing IoT

First, the Internet of Things is about adding convenience, not solving a universal problem. People look at IoT and instinctively react by asking “Why do I need that?” This type of technology product always suffers from a slower adoption rate. With such a slow adoption rate, it is hard for companies to justify the expense in working with other companies to engineer a common framework. For established companies this would entail reworking entire product lines that are already making money. Startups might be more likely to adopt a common protocol, but they lack the ability to influence larger, more proprietary-minded corporations to do the same. Adding to the lethargy of the adoption rate, the process of standards development is time-consuming (just look at the revision history for 802.11 WiFi). Standards development also requires compromise that a lean, idealistic startup might not have the resources to support.

Although we are slowly seeing the slow transformation of cable television into television over IP with the advent of services such as SlingTV and HBO Go, the IoT may have to gestate slowly until there is a cultural shift or a very innovative, must-have product that demands a level of interoperability impossible for companies to ignore.

To be sure, there are other technical barriers in addition to the market and common communication protocol issues. Given the sheer number of potential connected things, the Internet will have to adopt IPv6 which provide for approximately 3.4 x 1038uniquely addressable devices. Comparatively speaking, it is estimated that in all the world’s beaches there are only 7.500 x 1018 grains of sand. The current IPv4 allows for a mere four billion addresses. There is also a data storage issue: How much new data will be generated that needs to be stored, even if only temporarily? This is not readily known but will no doubt be very significant. Today, existing barriers are somewhat mitigated by industries that are adding new data centers at breakneck speed.

A Ba-zillion Points of Light

The Internet of Things is a bold, potentially game-changing concept: a “smart” world that, without human interaction, can create significant convenience for people. Furthermore, IoT will be a key enabler of other game-changing developments such as the smart electric grid. Home appliances such as a washer and dryer will be able to schedule their own start times after “consulting” with the local utility provider about what time of day has the cheapest electric rates. At that point, the IoT becomes more than just a convenience and starts to become responsible for good energy stewardship and financial savings. That is a powerful concept.

To be sure, the Internet of Things has a great deal of promise. According to Cisco’s CE, IoT will garner a $19 trillion marketplace. IoT will take an unprecedented level of cooperation, not competition, to be fully realized. If we are successful, in the coming years we could begin to see thousands of new smart devices that will dwarf the current craze of smartphones, smart TVs, and smartwatches; cutting costs and reducing environmental impact. IoT can help blaze a trail to a brave new world of not just convenience, but to one where we can become better economic and ecological stewards without lifting a finger; that is, if we can find a way coalesce the thousands of industry protocols and overcome the other obstacles to build a true Internet of Things.